UPDATED

“Livestock are responsible for 18 percent of the greenhouse gases that cause global warming more than cars, planes and all other forms of transport put together. It’s official: taking to the roads in an SUV’s got nothing on cattle flatulence . . . “ This is a direct quote from a recent web post of a climate sceptic. It restates a popular meme about climate change, favoured by conservative commentators: that man isn’t the most important agent of global warming, it’s the farting cows, stupid. This begs the question of why the cows are there in the first place—presumably not just to control the growth of grass on pasturelands. In the parlance, that meme is bullshit, but it’s also true that the gas central to it, methane, is a serious threat to global climate.

Before doing my homework on this piece, I believed the climate scientists, who say that the climate is changing, and on a global scale, that temperatures are going up. I further accepted that things are changing for the worse even faster than was thought a few years ago. And I also suspected that the scientists are right in predicting that there’s nothing we can do to prevent some unpleasant changes. After doing my homework, I hold those beliefs even more tightly. If those positions are unacceptable for you, stop reading and go back to watching Fox News. But what I had previously failed to grasp was the importance of methane as a greenhouse gas.

The things people believe about climate change

People’s beliefs about climate change are on a spectrum. At one end of the spectrum, what we might call Out to the Right, there’s outright denial that anything untoward is happening: climate changes all the time, the OutRights say, and we happen to be in a cycle that’s trending warmer at the moment. We’ll soon be complaining about cool summers. A little to the left of that position, we have grudging acceptance that climate is changing, and not in a good way, but it’s due to some extrinsic forcing we have no control over: sunspots are a favourite.

People who believe that it’s getting warmer globally because of human activity occupy the centre and left end of the spectrum. Just to the left of centre are those who agree that climate is changing, but believe that technology can ‘fix’ things without inconveniencing us too much. To their left are people who accept that minimizing the damage is going to take a herculean effort, including vegetarianism or veganism, drastically reducing consumption of natural resources, and other efforts that reduce the emission of greenhouse gases (GHG).

And there are people from all parts of the rainbow who think that cow farts are driving global warming. My initial instinct was that that meme surely didn’t pass the smell test, but in investigating the story, I came upon some unsettling truths. Among them, that raising cows makes a non-trivial contribution to greenhouse gases.

It’s complicated

Without a blanket of greenhouse gases, there would be none of the life we see on earth—the average temperature would be around -18ºC, instead of the present 15ºC. GHG trap radiant solar energy and cause temperatures to rise. But rising levels of greenhouse gases are driving unwanted climate change, with the most important change being the level of carbon dioxide (CO2). (Water vapour is a very important GHG, but its quantitative effects, and potential for change, are not yet well determined. Because warming leads to increased water vapour in the atmosphere, there may be a positive feedback loop between rising global temperatures and water vapour, which could add to the problem.)

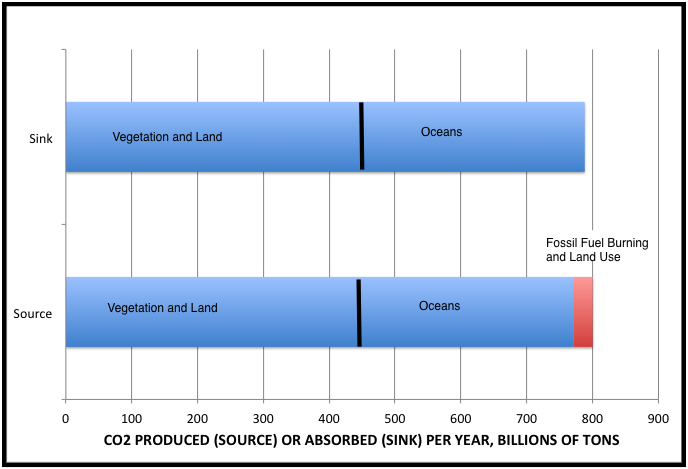

The CO2 level in the atmosphere is the result of the balance between its production and absorption. Natural sources that generate atmospheric CO2, and natural sinks which absorb it, are by far the most important quantitatively, as the following graph shows. Of the total CO2 produced or absorbed each year by the natural environment, about 57% is land-based, the rest being due to exchange with the ocean.

Anthropogenic (human) activity, such as the burning of fossil fuels and the effects of land use, account for only a small fraction of the global CO2 budget. However, anthropogenic greenhouse gases tip the balance of nature, making the source of CO2 larger than the sink. If the anthropogenic source were sufficiently small, the atmospheric CO2 level would sink to pre-industrial levels with natural sinks and sources in equilibrium.

During historical periods of heavy glaciation, a lot of CO2 was trapped in the oceans, and balance was achieved at around 180 parts per million of CO2 in the atmosphere. Between glaciations, the CO2 level goes up—in the pre-industrial world it was around 280 parts per million. It has just passed 400. That’s why climate scientists are concerned. It’s high and rising, and the known physics says that will cause further global warming.

Carbon dioxide is not the only greenhouse gas

After water vapour and CO2, methane is the most important GHG. Methane contributes to global warming to a greater extent than its low concentration would suggest. That’s because methane is a much more effective greenhouse gas than CO2: how much more effective is difficult to determine precisely. The figure accepted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2014 was 28: one kilogram of methane has as much “global warming potential” as 28 kilograms of CO2. It estimates that one kilogram of methane put into the air today will have a global warming effect, over the next 100 years, equivalent to 28 kilograms of CO2 released today.

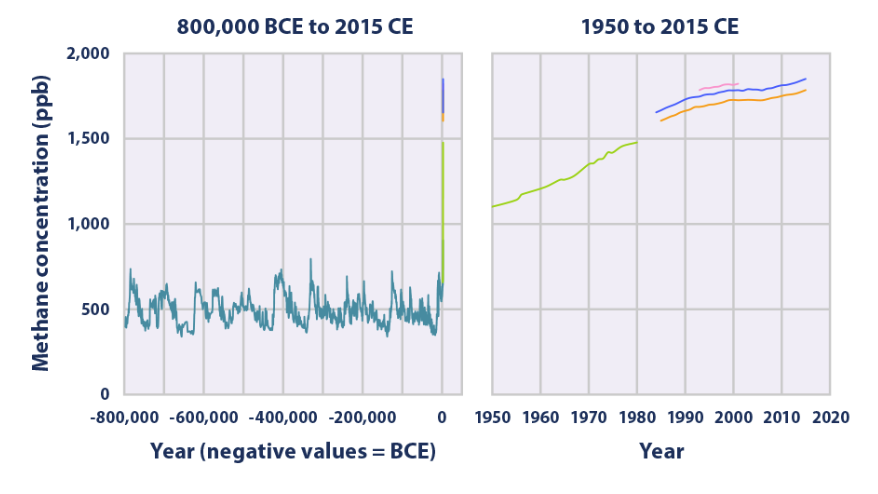

Some sources of information use a lower number for the global warming potential of methane, some use a much higher one (over 80 in some cases). The difficulty of accurately measuring the potency of methane relative to CO2 stems from their different fates in the atmosphere. Methane has a limited half-life, 10 years or less, while CO2 lasts almost forever. Methane is broken down to CO2 by hydroxyl radicals in the atmosphere. But this system of degradation may be failing, as seen by the continually rising level of methane (below).

In talking about the effects of methane and other GHG, the term of art is CO2e, which stands for “carbon dioxide equivalent”. By that convention, the IPCC gives methane a rating of 28 CO2e.

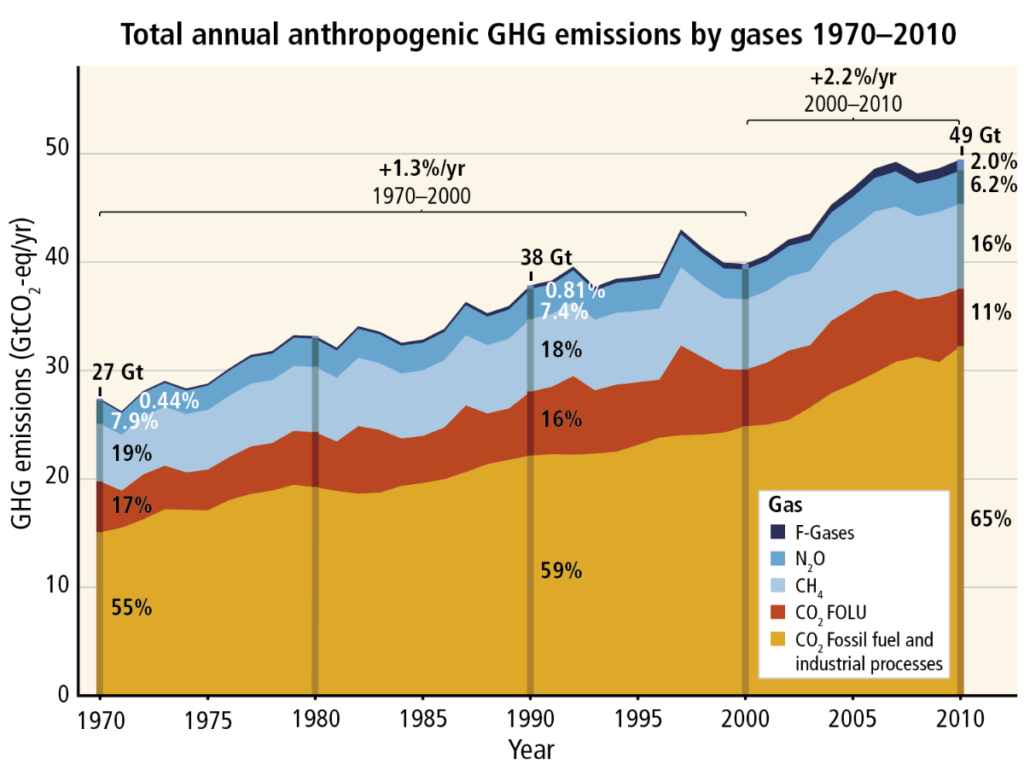

The total effect of all anthropogenic greenhouse gases on the climate is compared and summed up in the following graph. The top line represents the total annual anthropogenic GHG emission, in CO2e. By 2010, it had reached 50 billion metric tonnes of CO2, or 50 GtCO2e (Gt stands for “gigatonnes”). The red bar on the previous graph (“Atmospheric sources and sinks of CO2”) represents only about 76% of the total GHG; methane adds another 16.4% (8.2 GtCO2e) in 2010. Other anthropogenic gases complete the picture.

The eructation and flatulation of cows

Cows are complicated creatures, with some useful advantages for humans, such as producing milk. But their convoluted way of digesting food presents a problem for the global climate. Their stomachs have four compartments, and newly cropped grass enters the first two of these for bacterial fermentation: cows depend on enzymes of bacteria to digest cellulose. The solids from these compartments are regurgitated as cud for further physical breakdown. The bacterial action, “enteric fermentation”, takes place in an oxygen-free environment, which leads to the production of methane, lots of it.

Most of the methane produced by enteric fermentation in cows and other ruminants (sheep, goats, deer, giraffes, and some other creatures) is emitted as burps, “eructation”. Only about 5% is given off in flatulence, farts if you will. Its effects are the same in either case, and they are significant.

The enteric methane produced by the world’s 1.3 – 1.5 billion bovines has been estimated as contributing 20-25% of total anthropogenic methane (1, 2). From the graph above, that total was about 8 GtCO2e for 2010. That means cows’ burps were responsible for between 1.6 and 2.0 GtCO2e. The total CO2e was about 50 Gt that year, so cattle burps contributed around 3.6% of the total GHG effect. Transportation produces about 14% worldwide. (The production of cement contributes 4-8%.) This is not trivial, and will be explored in more detail in another post, but enough already with cow farts being more damaging to the environment than transportation.

Incidentally, that meme was probably derived using something like the following logic: cow farts contain methane, methane contributes about 16% of the total GHG effect, ergo cows contribute more than transportation (14%). But most methane comes from other sources, not directly from cows.

Vegetarians are right

Although the contribution of cows’ methane production to GHG is sometimes overstated, I do think vegetarians are on the right side of history. Meat production is simply too expensive, in every way: energy input (fossil fuel to produce cattle feed, use of land), GHG emissions (including emissions due to clearing of ever more land for pasture and feed growth), and water consumption (several times higher, per calorie, than for equal numbers of plant-based calories directly consumed). Perhaps a small amount of meat could still be part of the diet, but not as much beef as at the current North American levels. Vegans . . . I’m not sure, perhaps because I’d hate to give up eggs and dairy products. Surely we can develop humane and efficient ways of producing these foods? On the other hand, The Economist has declared 2019 the year of the vegan

If dairy is kept in the diet, that will require some cows (goats produce more methane per liter of milk than cows). But surprisingly few. About 98 million bovines live in the USA today, most of them dedicated to building up their muscles so that they can be killed and eaten. To produce the amount of milk and other dairy products currently consumed would require only about 7 million healthy and properly-fed milk cows. Importantly, diet and health influence the ratio of milk yield to methane produced (1), as will be explored in a later post. There would have to be a few bulls, too, but saved sperm works fine, reducing the need for live bulls. The methane production would be at least 90% less than currently from beef.

We need to worry about methane

In prehistoric times, methane was present in the atmosphere at between 400 and 700 parts per billion (ppb). (More than 2 billion years ago, there may have been a period when the methane level in earth’s atmosphere was very high.) In the past million years, methane was probably mainly produced by anaerobic bacteria. But in recent times, it has gone up, as the increasing rate of production has overwhelmed the natural process of degradation by atmospheric hydroxyl radicals. In addition to sources related to industrial processes such as the production of fossil fuels, methane produced in agriculture is important. For a short time in the 1990s, methane levels stopped increasing, probably as a result of a levelling off in related economic activity (3). But now they are on the march again, for reasons we don’t fully understand.

Recent research tells us that the level of leakage of methane from natural gas wells and the delivery infrastructure (pipes, valves, storage tanks) is higher by 60% than previously thought. A recent study using satellite data estimates that short, large-scale bursts during production and transportation of methane contribute 12% of global methane leakage. So on the one hand, the use of natural gas in power plants has reduced the CO2e emissions, on the other, methane escaping to the atmosphere has increased the greenhouse effect. The good news is that the rate of leakage from the producing technology could be fixed at relatively low cost, cost which might be met from the recovered methane. But it may require government regulation to get this to happen.

Among the human activities that are increasing methane is the clearing of forests for agricultural use (which also increases atmospheric CO2), rice growing, fracking (leakage of methane to the atmosphere is greater than previously thought), and, yes, the raising of domestic animals such as cows. The digestive systems of animals with simpler stomachs, like us, also produce methane, but at relatively low levels.

The 35-40% of methane production that is not due to human activity comes from sources such as wetlands (anaerobic fermentation, similar to what happens in the cow’s rumen), and microbes living in termites (!) and in the ocean.

Scientists are also concerned about the positive feedback loop produced through global warming’s effect on methane trapped in melting Arctic permafrost. The possible magnitude of this phenomenon is not yet accurately predictable. In addition, there is methane trapped in methane-ice crystalline structures at the bottom of the ocean in certain locations. Climate warming will bring some of these to the surface, but the amount of methane that could be released is, again, uncertain.

Anthropogenic methane production, like CO2, must be reduced for earth to remain human friendly. Probably the only practical way to achieve this is by applying reductions incrementally but fairly promptly: lowering the consumption of fossil fuels by building alternative energy sources and imposing carbon taxes and higher vehicle efficiencies, for example. Rice can be grown without flooding the land, which reduces methane production. Meat consumption needs to be reduced, not so much because of the enteric fermentation of ruminants, but because meat production costs a lot of energy and produces GHG, including some due to clearing land to grow feed. If the phenomenal amount of food being wasted were reduced, the energy consumption in agriculture and transportation would be reduced also. The list of useful incremental changes is long.

——————————————————

The geophysicist Dr. Wallace Smith Broecker died on February 18 of this year. Back in 1975, Dr. Broecker popularized the term ‘global warming‘ when he published a paper titled, “Climate Change: Are we on the Brink of a Pronounced Global Warming?” This captured the emerging scientific consensus that global warming was likely going to happen because of the buildup of greenhouse gases. He is quoted as saying that ”the climate system is an angry beast and we are poking it with sticks.”

Go To Contents

Sources

- Lassey et al., Aust. J. Exptl. Ag. (2008) 48:114.

- Herrerro et al., (2013) Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 110(52): 20888.

- Bousquet et al., (2006) Nature Sep 28;443(7110):405

Hi Vern,

I’ve just chanced in your website and like what I see.

The first article I read is your April methane one. Methane is a hot topic where I come from, New Zealand, where dairy (largely pasture fed) is a massive part of our economy, and under GWP100 ratings agriculture accounts for around a whopping 48% of our gross national GHG emissions.

I’ve got more info to share than I can put in this comment, but if you’re interested please email me and I’ll be pleased to respond more fully. The info I have is not in major conflict with what you’ve written.

Many thanks.