As we people of the modern world grow heavier by the year, we have developed a growing interest in our morbid obesity. Or a morbid interest in our growing obesity. Our curiosity is justified: obesity is firmly linked to poor health. As a result, there’s a massive, and growing, industry dedicated to helping us, or at least promising to help us, lose weight. But like most stories about metabolism, it’s complicated. One aspect that is not well understood is the relationship of exercise, physical exertion, to obesity. Here are some bits about obesity and exercise you may not know. First some history.

The Frenchman Jean Mayer

When I was a graduate student, in a previous Millenium, I came across an intriguing scientific report. It showed an unexpected effect of exercise on energy metabolism, which I was studying as a graduate student. The work was done by a research group at Harvard University under the direction of one Professor Jean Mayer.

Mayer was born in France, the son of scientifically distinguished parents. At 17, he earned a B. Litt. degree, summa cum laude, in philosophy, from the University of Paris. At 18, a second degree, in Mathematics. And at 19, an M. Sc. in Biology. That same year he was accepted as one of only 20 students from across France to study at the elite Ecole Normale Superiore. When World War II broke out that year, he enlisted as a gunner in the French army, and his unit helped protect the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force, a critical event in the war. He was captured, but escaped after shooting a guard. As the French army had by then surrendered, he joined General de Gaulle’s Free French Army, and served both at sea and in North Africa. Mayer landed south of Naples with the Free French as part of the US Fifth Army, and then in the south of France after D-day, both scenes of heavy fighting. At the end of the War he was awarded 14 decorations for his wartime service, including the Croix de Guerre with palms (twice), and the Legion d’honneur. A remarkable warrior record for a short, slight, considerate man known for his charm and sense of humour. He was 25.

After the war Mayer applied for and received a grant to study in the USA (in addition to being attracted to study science in the USA, he had met and married a young woman there during the war). He obtained a Ph. D. in Physiological Chemistry at Yale University in 1948. In 1950 he became a professor at Harvard, and for the next 27 years he carried out research there on the regulation of food intake, for which he attracted great recognition.

Mayer was an effective leader and organizer, as well as a brilliant scientist. After his career at Harvard, he was tapped to become President of Tufts University, where he proceeded to build research capabilities and prestige there. He was an advisor to Presidents Nixon, Ford, and Carter, and was awarded 21 honorary degrees from American and other universities. A remarkable man.

Jean Mayer’s Racing Rats

The publication from Mayer’s lab that caught my eye in 1965 was about rats on a treadmill (Mayer et al., 1954). One of Mayer’s lifelong scientific interests was to understand how appetite is regulated; what causes us to eat exactly enough to sustain us and provide the energy to do our work? As a lot of nutritional studies did (and still do), he studied the question in rats. He asked what the relationship would be, between the amount of work rats did, and the amount they ate. The standard answer was, that rats would eat an amount that was proportional to their activity. To look at this more closely, Mayer had his assistant build a rat-sized treadmill (shown at the top of this post) that was driven by a motor, which would force the rats to do a controlled amount of work for a defined period of time each day. (The animals were given a two-minute rest after every 5 minutes.)

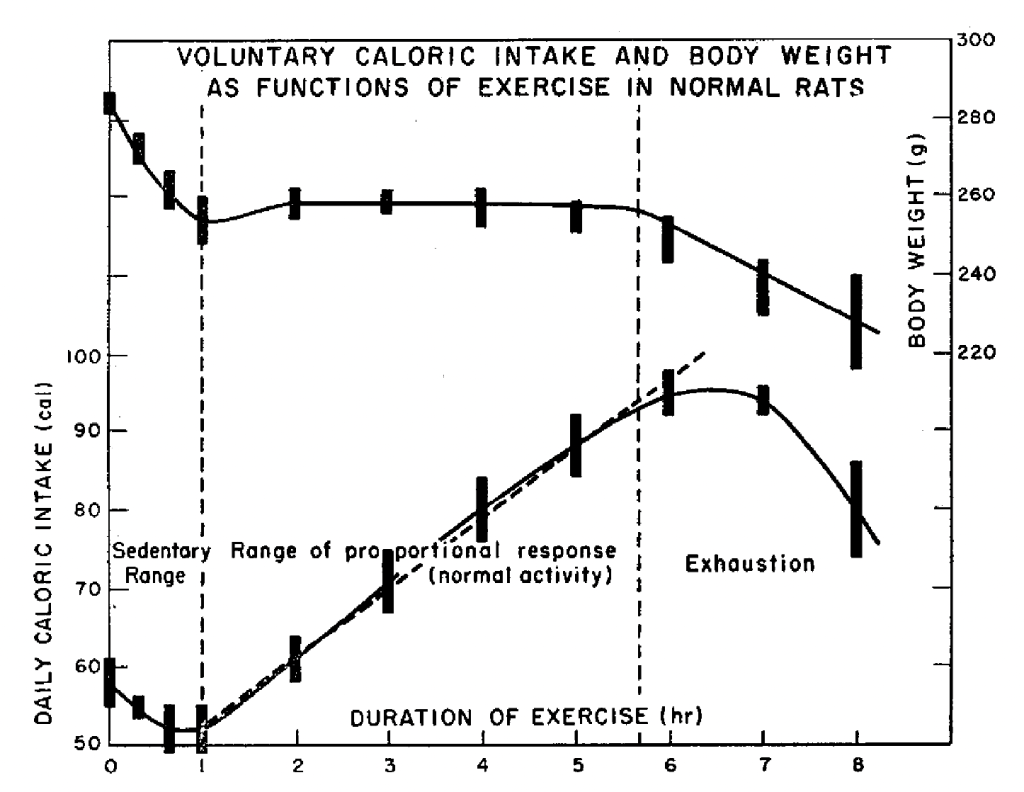

What Mayer and his students observed was that when rats were exercised for more than an hour, they would eat more, in proportion to their increased workload. Their body weight remained constant. The conventional wisdom got that part right. But at very low, or zero, work (less than an hour a day on the treadmill), food consumption didn’t go down, it went up a little, as did the weight of the rats. In other words, below a certain work rate, the body’s controls no longer worked, and the rats got a little fat. He called this low energy state the “sedentary range”. Food intake and body weight as functions of duration of exercise in rats. The top line shows the amount the rats, which were allowed to eat ad lib, ate. The bottom line shows the amount of work they were forced to do, as shown by the number of hours they worked (bottom axis). The surprising result was that at very low, or completely sedentary, conditions, the rats ate a little more than at a higher level or duration of exercise (1 hour), and also put on extra weight.

Food intake and body weight as functions of duration of exercise in rats. The top line shows the amount the rats, which were allowed to eat ad lib, ate. The bottom line shows the amount of work they were forced to do, as shown by the number of hours they worked (bottom axis). The surprising result was that at very low, or completely sedentary, conditions, the rats ate a little more than at a higher level or duration of exercise (1 hour), and also put on extra weight.

Mayer wanted to know if humans also experienced this uncoupling of food intake and activity at very low work rates; did we also had a ‘sedentary range’. He investigated this question in Chengail, West Bengal, India, where his group studied the activity – weight range of workers in a large jute factory. What they found corresponded to what you would have predicted from the rat study. Whereas the workers who carried the heavy bags of jute, or did other hard work, all weighed between 110 and 120 pounds, the fully sedentary ‘stallholders’, record-keepers whom Mayer described as almost completely stationary in their chairs, weighed 50 pounds more (Mayer et al., 1956, as quoted in Herman Pontzer’s book ‘Burn’, which is the best book I’ve seen on human energy metabolism). Of course, there could be other explanations, but the most likely one is that, like the rats, an almost total lack of exercise in humans knocked the normal appetite controls out, and led to overeating. Lesson one.

Walking and working

As you’re reading this, you are probably engaged in one of the unhealthiest normal practices of the modern age: you’re sitting in a chair. Maybe not. Maybe you are walking slowly, slowly, along an infinite path that promises to deliver a healthier reading journey. I’m talking about walking on a treadmill desk while doing a mental task, such as reading this post. Treadmill desks became a thing in the early twenty-first century, when the idea was popularized by Dr. James Levine, a doctor at the Mayo Clinic. Concerned about being sedentary so much of the time, he put a hospital tray onto the arms of a conventional treadmill and carried out some of his office duties while slowly walking.

Treadmill desks had been constructed before, but Dr. Levine promoted them successfully, and several companies began to produce integrated treadmill-desk units. Typically, the worker walks at a slow pace, maybe 2-3 kilometer per hour, as they carry out their office tasks.

Dr. Levine was trying to overcome the unhealthy effect of spending too much time sitting down, which many of us do. Over-sedentarity is thought to increase the risk of heart disease, diabetes, and particularly obesity. He felt that walking slowly on a treadmill, while attending to activities on a suitably raised desk, was good for him. But treadmill desks have had a limited impact for two reasons. First, if you’ve ever tried one, you will know that it’s hard to carry out physical actions while walking. You can read the New York Times just fine, but it’s hard to fill in a spreadsheet. Also, some people find, as I have, that focusing on difficult mental problems is also harder while treadmilling.

Do treadmill desks improve health?

Most people who use treadmill desks, not surprisingly, claim that they make them feel better. That effort and slight discomfort must do some good! There is also some evidence in the medical literature for improvements in health, but it’s not overwhelming. There’s little evidence for weight loss for average people. That’s unsurprising, since the one- or two-hundred kilocalories expended each day on the treadmill, less than 5% of most people’s caloric food intake, simply causes most people to eat just a little bit more to make up the difference. But in one of Levine’s studies, obese people who went on the treadmill desks did lose some weight – about 2.3 kilograms (5 pounds) over a year (Koepp et al., 2013). Normal-weight people did not lose a significant amount of weight, but some cardiometabolic markers, such as blood pressure, and the glucose and insulin responses and triglyceride levels after eating, were lower (Champion et al., 2018) To be accurate, not every study agrees with this beneficial outcome (Oye-Somefun et al., 2021).

Maybe treadmill desks are doing the same thing for normally sedentary office workers as the treadmills did for Mayer’s rats, keeping people just out of the sedentary range?

Physical activity as an antidote for obesity

As beneficial as exercise is for many reasons, it is almost impossible to overcome obesity over the long term by exercise alone. That requires a higher level of dedication and discipline than most people bring to the table. But exercise plus diet control can be a more effective weight-loss scheme than either alone. A study published in 1989 found that severe dietary restriction over two months caused an average 25 pound weight loss for a group of Boston policemen (Pavlou et al., 1989, also as quoted in Pontzer’s book). Half of them were also told to exercise. After the diet restrictions ended, the men who exercised maintained the weight loss for at least 18 months (the end of the observations), while those who didn’t exercise gained back every pound.

An extreme example of the relationship of life-long physical exertion to obesity is provided by the Pima Indians, who I introduced in a previous post. There are two groups of Pimas, one in Arizona, the other in northern Mexico. Although they are the same genetically, their healths are very different. Until about 1900, both groups were subsistence farmers, with the Americans carefully husbanding water brought by the Gila and Salt Rivers to grow crops (they also harvested foods from their surroundings to supplement their farming). But beginning in the mid-19th century, their water began to disappear, as upstream farmers diverted the Gila and Salt Rivers for their own use. The promise to the Pima that they would be allowed sufficient water to continue farming was not kept, and by the beginning of the 20th century they could no longer grow crops, and were essentially dependent on American government surplus food to survive. They went from active subsistence farmers to sedentary welfare recipients.

At that point, the healths of the American and Mexican Pima began to diverge. While the Mexicans continued to live relatively healthy and fit lives, the American Pima went from well built, fit, individuals to become one of the most obese, and Type 2 diabetes-prone groups, in the world. A study published in 2000 documents the difference (Esparza et al., 2000). Some of the important differences between the two groups are summarized in this table.

. Averages for:

Mexican Pima Indians USA Pima Indians

Weight 66.5 kg (146 lb) 92.8 kg (204 lb)

Percentage body fat 29 41

Body fat mass 19kg (42lb) 38kg (84 lb)

Total energy expenditure/day 3010 kcal 2940 kcal

Active energy expenditure/day 1243 kcal 711 kcal

To begin with, the Americans were far heavier, with much of the extra weight being fat. But the total food energy taken by the two groups each day was not that different, especially when the difference in ‘fat-free mass’ is considered (basal metabolic rate is proportional to fat-free mass). What really was different was the amount of Active Energy Expenditure (exercise, work) each day: the Mexican Pima expended on average 75% more. Is this the basis for their metabolic health? The authors take care to not overstate the case: typical of a good scientific conclusion, their title reads ‘Daily energy expenditure in Mexican and USA Pima Indians: low physical activity as a possible cause of obesity’. But I would put money on it.

From a survey of scientific reports, we can conclude that exercise or diet alone are very hard ways for an adult to go from being overweight or obese to a more normal body type. But the experience of the Pima Indians shows, I think, that a life that involves a high level of active energy expenditure throughout does lead to a healthier weight. People generally reach a weight and food-input ‘set point’, which is a function of genetics and daily food intake, and it’s then difficult to move away from that point; it takes persistent, consistent, effort over a long time.

Work cited

Mayer, J. et al. (1954). Exercise, Food Intake and Body Weight in Normal Rats and Genetically Obese Adult Mice, Amer. J. Physiol. 177(3) 544-548.

Mayer, J., P. Roy, and K. P. Mitra (1956). Relation Between Caloric Intake, Body Weight, and Physical Work: Studies in an Industrial Male Population in West Bengal, Amer. J. Clin. Nutrition 4(2) 169-175.

Pontzer, H. (2021). Burn: New Research Blows the Lid Off How We Really Burn Calories, Lose Weight, and Stay Healthy, Penguin Random House.

Koepp et al. (2013). Treadmill desks: A 1-year prospective trial, Obesity 21(4) 705-711.

Champion et al. (2018). Reducing prolonged sedentary time using a treadmill desk acutely improves cardiometabolic risk markers in male and female adults. J. Sports Sci. (2018) 36(21):2484-2491.

Oye-Somefun et al. (2021). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Treadmill Desks on Energy Expenditure, Sitting Time and Cardiometabolic Health in Adults, BMC Public Health 21:2082-2090.

Pavlou, K. N., S. Krey, and W. P. Steffee (1989). Exercise as an Adjunct to Weight Loss and Maintenance in Moderately Obese Subjects. Amer. J. Clin. Nutrition 49(5):1115-1123.

Esparza, J. et al., (2000). Daily Energy Expenditure in Mexican and USA Pima Indians: Low Physical Activity as a Possible Cause of Obesity. Int. J. Obesity 24:55-59.