A mild tremor went through the blogosphere when Coca Cola announced that it would soon re-introduce Coke containing cane sugar in the USA. In recent times, Coke USA has used sugar derived from corn starch, so-called High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS), rather than sugar isolated from sugar cane. Many applauded Coca Cola’s move, and proclaimed it to be beneficial to the nations’s health.The consumer-in-chief D. J. Trump had urged this move earlier in the year.

What is healthy sugar consumption?

The interest in the switch from HFCS to cane sugar in the USA can be linked to a publication in 2004 (1) which proposed that HFCS promotes obesity. That idea soon took on a life of its own, and a widely held current opinion is that HFCS has a greater ability to cause obesity than cane sugar. In answer to the question ‘Does HFCS cause obesity?’, Professor Google, calling on the gods of AI, says: ‘Yes, excessive high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) consumption is linked to obesity, though it’s controversial whether HFCS has a unique role compared to other sugars.’ The real question is, ‘Does HFCS, on a calorie or weight basis, cause more obesity than cane sugar?’. Dr. Google’s answer to that one (check it out) is really adrift, as the following will illustrate.

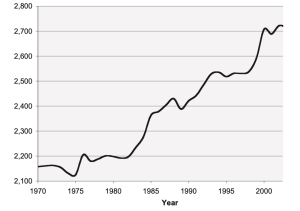

The paper that originally suggested the HFCS-obesity link was an hypothesis: it contained no data that supported a unique obesogenic effects of HFCS. It was based on the correlation between increasing obesity and HFCS consumption in the USA. But that correlational link broke down many years ago: the consumption of HFCS has declined by about 45% since it peaked in 1998, but the level of obesity, sadly, has continued to rise since then, by about 40%. The rise in obesity, as I have described elsewhere, is undoubtedly due to the rising consumption of food. The intake of calories is illustrated by this graph: per capita calorie consumption in the USA increased by about 25% between 1970 and 2008, and the level of obesity has increased by about 170%. All that increased foodstuff had to go somewhere, and that somewhere was human fat.

FIGURE 1. Per capita daily caloric intake in the USA (US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service)

The 2004 hypothesis about an obesity-HFCS link let loose the dogs of nutritional hysteria. The popular site ‘Healthline’ boldly starts an article about HFCS with ‘6 Reasons Why High-Fructose Corn Syrup Is Bad For You’. A favoured explanation for an HFCS – obesity link is that, based on known metabolic pathways, fructose is more likely than cane sugar (sucrose) to be converted to fat in the human body. That ‘explanation’ makes no sense, as will be explained.

Meanwhile, nutritional scientists, not wanting to leave any stone unturned, looked for a unique HFCS – obesity link — maybe there was another, yet unknown, component in HFCS that somehow stimulated fat production? So studies were organized, and data were collected. And the data did not support the hypothesis.

As an example, a paper published in 2007 found no difference between HFCS and sucrose on energy intake, fasting plasma glucose and insulin levels, or the levels of the weight-regulating hormones leptin and ghrelin (2). A review of the HFCS-health link in 2013 (3) concluded that HFCS and sucrose (cane sugar) have the same effects on obesity. No difference. Not surprising, considering what comes next in this piece.

In answer to the question posed by the heading of this section, the healthiest sugar consumption for most people has a quantitative, not a qualitative answer: eat less sugar, from whatever source.

OK, What is HFCS?

Corn, like many plants, stores starch in its seeds to feed the little seedlings when they germinate. Corn starch, like other starches, including the glycogen stored in our muscles, contains the sugar glucose, and nothing else. It is the starting material for HFCS.

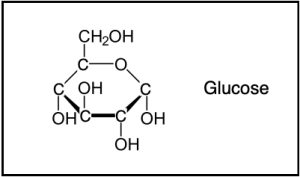

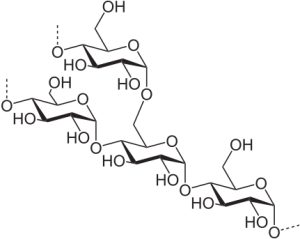

Glucose is a ‘monosaccharide’, one simple sugar molecule. Starch is a ‘polysaccharide’ — many glucose residues chemically joined together. These glucose residues are joined head-to-tail in long chains, with an occasional branch point that starts another chain (there are both branched and un-branched starches). The number of glucose molecules in a corn starch particle can be in the millions. A small fragment would look something like this, where the glucose molecules have been written in a form that more accurately reflects their actual shape in space:

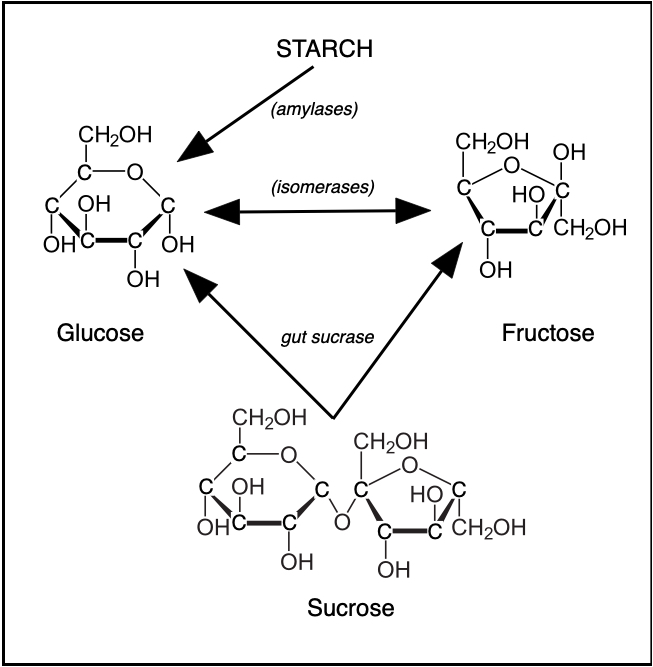

To produce HFCS from corn starch, the starch is cleaned up and then treated with enzymes (‘amylases’) that ultimately liberate free glucose (the actual process is messier, and includes other chemicals). Then the glucose syrup is treated with another enzyme, an ‘isomerase’, which converts about 42% of the glucose to fructose. Glucose and fructose have about the same free energy, so the addition of an enzyme, a protein catalyst, that allows them to interconvert, produces this ratio of fructose to glucose spontaneously. The fructose produced is then separated from the glucose as ‘HFCS90’ (90% fructose, 10% glucose). HFCS 90 is then mixed with glucose to form either HFCS55 (55% fructose) or HFCS42 (yes). These are what is known as ‘High Fructose Corn Syrups’. Not really that high.

In fact, the HFCSs produced from corn starch are about the same as what is produced by digestive enzymes in our guts from the sugar in sugarcane or sugar beets. Sucrose is a ‘disaccharide’ — it contains one molecule each of glucose and its closely related cousin fructose. During digestion, an enzyme (‘sucrase’) cleaves the bond between glucose and fructose in sucrose and releases an equal part mixture of the two. In other words HFCS50. Fructose and glucose are then absorbed into the bloodstream, and go on their merry metabolic meandering. The relationships between starch, sucrose, and glucose and fructose are illustrated in the figure.

Much of the confusion about HFCS is caused by the name: ‘High Fructose’. But the HFCS used in drinks contains 55% fructose and 45% glucose (as well as some water). The HFCS used for sweetening other foods contains 45% fructose (and 55% glucose).

HFCS exists for the oldest of reasons: it’s cheap, at least in the USA, where corn growing is heavily subsidized. The reasons for this subsidy are several, including the concern that a lot of cane sugar is imported (tariffs!), and it was thought that ethanol made from corn syrup would reduce the CO2 output from the transportation industry (it doesn’t). But once in place, a subsidy is almost impossible to remove, so we have HFCS being produced at a lower cost than (imported) cane sugar. DJT must be pleased.

But the nutritionally-concerned have it right in preferring sucrose: using HFCS rather than cane sugar (as is done in Coke made in Mexico) involves farming subsidies (over 3 billion dollars a year), and unpleasant industrial processes. But HFCS doesn’t pose a unique health problem.

As a final wrinkle, acidic beverages (like Coke) cause sucrose to begin to hydrolyze spontaneously, just like sucrase does in the figure above. So even if the Coke was originally sweetened with sucrose, it ends up quite similar to HFCS – a mix of fructose and glucose. Pre-digested.

Meanwhile, since everything today has a political component, Jeffrey A. Singer, Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute, writes:

“In a post on X, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., cheered Tyson Foods Company’s decision to drop high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) from its branded products by the end of this year. He wrote, “I call on every food company to follow your lead and join the movement to Make America Healthy Again.”

The problem with that post is that nothing supports the secretary’s claim that replacing HFCS with sucrose makes you healthier. The published, peer-reviewed science shows that your body processes them the same way, and that too much of either is harmful.

Work cited

(1) Bray GA, Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. (2004) Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr, 79: 537-543.

(2) Melanson KJ, Zukley L, Lowndes J, Nguyen V, Angelopoulos TJ, Rippe JM. (2007) Effects of high-fructose corn syrup and sucrose consumption on circulating glucose, insulin, leptin, and ghrelin and on appetite in normal-weight women. Nutrition, 23:103–12.

(3) Rippe, JM, Angelopoulos TJ. (2013) Sucrose, High-Fructose Corn Syrup, and Fructose, Their Metabolism and Potential Health Effects: What Do We Really Know? Adv Nutr 4(2): 236-245.